Curriculum

- 12 Sections

- 69 Lessons

- 100 Hours

- Chapter 1 (Solid State)4

- Chapter 2 (Solutions)10

- 2.0Types of solutions20 Minutes

- 2.1Ways of expressing concentrations 120 Minutes

- 2.2Ways of expressing concentrations 220 Minutes

- 2.3Henry’s Law and applications 120 Minutes

- 2.4Raoult’s Law and applications 220 Minutes

- 2.5Colligative property 110 Minutes

- 2.6Colligative property 215 Minutes

- 2.7Colligative property 315 Minutes

- 2.8Colligative property 415 Minutes

- 2.9Abnormal Molecular Mass15 Minutes

- Chapter 3 (Electro Chemistry)8

- 3.1Electrolytic conductivity 120 Minutes

- 3.2Debye Huckel limiting law15 Minutes

- 3.3Electrochemical Cell20 Minutes

- 3.4Cell potential in electrochemistry20 Minutes

- 3.5How to use Nernst equation20 Minutes

- 3.6Gibbs free energy in electrochemistry20 Minutes

- 3.7Understand Faradays Laws of Electrolysis20 Minutes

- 3.8Fundamentals of commercial batteries20 Minutes

- Chapter 4 (Chemical Kinetics)6

- 4.1How to calculate rate of reaction20 Minutes

- 4.2How to calculate reaction law and orders20 Minutes

- 4.3Initial rate method know it all faster15 Minutes

- 4.4How to use integral method in kinetics 120 Minutes

- 4.5How to use integral method in kinetics 215 Minutes

- 4.6How Collision Theory Explains Chemical Reactions20 Minutes

- Chapter 8 (d-block Elements)7

- 5.1d block electron configuration charts10 Minutes

- 5.2Trend across d block 1 atomic radii10 Minutes

- 5.3Trend across d block 2 melting point10 Minutes

- 5.4Trend across d block 3 Ionization energy10 Minutes

- 5.5Trend across d block 4 Oxidation state10 Minutes

- 5.6Trend in d block 5 Electrode Potential10 Minutes

- 5.7Trend in d block metal properties

- Chapter 9 (Co-ordinate Compounds)6

- Chapter 10 (Haloalkanes Haloarenes)7

- Chapter 11 (Alcohols, Phenols Ethers)7

- Chapter 12 (Aldehyde Ketones)4

- Chapter 12 (Carboxylic acid, Derivatives)3

- Chapter 13 (Amines)3

- Chapter 14 (Biomolecules)4

Fundamentals of commercial batteries

Fundamentals of commercial batteries

Table of Contents

Introduction

In our rapidly evolving technological landscape, understanding the fundamentals of commercial batteries is more essential than ever. From powering our smartphones to enabling electric vehicles, the various types of batteries play a crucial role in our daily lives and the wider economy.

This blog post delves into the core concepts surrounding commercial batteries, exploring the distinctions between primary cells, secondary cells, and fuel cells. Whether you’re a student, a budding engineer, or just a curious mind keen to learn about sustainable energy solutions, join us as we unpack the intricacies of these power sources and their significant impact on modern technology.

With insights and clarity, we aim to equip you with the knowledge needed to navigate the world of batteries confidently.

Fundamentals of commercial batteries: Primary cells

When it comes to understanding the “Fundamentals of commercial batteries”, the primary cell, particularly the dry cell, stands out as a cornerstone of portable energy solutions. The dry cell battery, often recognized by the iconic cylindrical shape we associate with household batteries, is a foundational component in our daily lives.

Created in the late 19th century, this innovation revolutionized the way we harness and use electrical energy. The dry cell operates on the principle of electrochemical reactions, whereby an electrolyte is present in a paste form rather than a liquid. This unique feature makes it leak-proof, allowing it to be transported and used in various applications without the risk of spillage.

The chemical composition typically involves a zinc anode and a carbon rod cathode, with a manganese dioxide and ammonium chloride paste acting as the electrolyte. This simple yet effective design ensures a reliable source of energy for low-drain devices.

While primary cells are known for their one-time use—once drained, they cannot be recharged—the dry cell’s ability to provide a steady voltage makes it ideal for powering everyday items such as remote controls, flashlights, and toys.

The convenience and reliability of the dry cell battery have led to its widespread adoption, even in an age where rechargeable options are becoming increasingly popular. However, it’s essential to recognize that while primary cell dry cells are cost-effective and easy to use, they have limitations. Their energy capacity diminishes over time, even when not in use, due to chemical degradation. Awareness of these factors is crucial when selecting batteries for specific applications.

Understanding the mechanics and characteristics of primary cell dry cells not only empowers users to make informed choices but also paves the way for deeper insights into the “Fundamentals of commercial batteries”. Whether for personal use or industrial applications, the dry cell continues to be a vital player in the modern energy arena.

Second in the “Fundamentals of commercial batteries” is

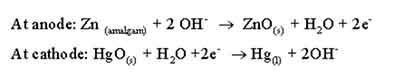

mercury cell. It has been a popular choice in various electronic devices before facing increased regulatory scrutiny due to environmental concerns regarding mercury toxicity.

Constructed from a combination of zinc and mercury oxide, the mercury cell typically offers a nominal voltage of 1.35 volts, providing a consistent and dependable power supply during its operational life. This characteristic of stable voltage makes it particularly well-suited for precision instruments, such as watches, hearing aids, and medical devices, where consistent power delivery is paramount.

One of the most appealing features of mercury cells is their long shelf life. Unlike many other primary cells that may degrade rapidly when stored for an extended period, mercury cells can retain their performance over time, making them a reliable choice for applications requiring minimal maintenance. Moreover, their compact design allows them to fit into small devices, providing power without compromising space.

However, it’s essential to acknowledge the environmental impact of mercury cells. Although their hazardous materials contribute to their efficiency and reliability, they also raise significant concerns when it comes to disposal and potential leakage. In response, many manufacturers and governments have implemented restrictions on the use of mercury in batteries, leading to the development of alternative solutions, such as alkaline and lithium cells.

While the mercury cell may be phased out in favor of safer options, understanding its functionality and history is critical to grasping the evolution of primary batteries. As we continue to explore the fundamentals of commercial batteries, the legacy of the mercury cell serves as a reminder of the balance between innovation and environmental responsibility.

Fundamentals of commercial batteries: Secondary cell

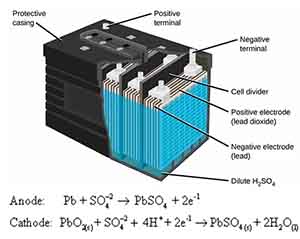

Lead storage batteries are a cornerstone of modern energy storage technology, renowned for their durability and versatility. Unlike primary cells, which are designed for single-use, secondary cells can be recharged and reused, making them a preferred choice for various applications from powering electric vehicles to serving as backup energy sources in homes and businesses.

At the heart of the lead storage battery is its robust design, which consists of lead dioxide (PbO2) as the positive plate, sponge lead (Pb) as the negative plate, and a sulfuric acid (H2SO4) electrolyte. This combination allows for efficient electrochemical reactions, enabling the battery to release and store energy effectively.

When the battery discharges, the lead dioxide and sponge lead react with the sulfuric acid to generate lead sulfate (PbSO4) and water, reversing the process during recharging to regenerate the original materials. One of the standout features of lead storage batteries is their ability to provide high discharge currents, making them ideal for applications that require a substantial amount of energy in a short time, such as starting internal combustion engines.

Additionally, they have a relatively low cost compared to other rechargeable batteries, and their technology is well understood, contributing to widespread adoption. Sustainability is also an important aspect of lead storage batteries. They are highly recyclable, with over 90% of the lead and other materials recoverable and reusable.

This makes them not only a practical choice but also an environmentally responsible one, reducing waste and the need for new raw materials. However, it is essential to monitor the maintenance of lead storage batteries, as they require regular checking of electrolyte levels and proper care to maximize their lifespan. When maintained correctly, these batteries can deliver reliable performance over numerous recharge cycles, making them a formidable option in the arena of energy storage solutions. In summary, secondary cells—specifically lead storage batteries—play a vital role in various industries and domestic applications.

Their rechargeable nature, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability make them an invaluable resource for anyone looking to implement efficient energy solutions. As we move towards a more electrified future, understanding and utilizing lead storage batteries will remain crucial in our pursuit of reliable energy storage.

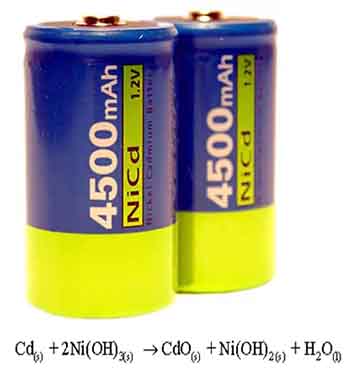

Fundamentals of commercial batteries Nickel Cadmium

Nickel Cadmium (NiCd) batteries have long been a staple in the realm of rechargeable energy solutions due to their robust performance and reliability. As a type of secondary cell, these batteries are designed for multiple charging cycles, making them an excellent choice for applications requiring consistent energy output and longevity.

A NiCd battery consists of nickel oxide hydroxide as the positive electrode and cadmium as the negative electrode. This composition provides several advantages: NiCd batteries are known for their ability to deliver a steady voltage throughout their discharge cycle, maintaining reliable performance even under high-drain conditions. This makes them particularly suitable for powering power tools, emergency lighting, and medical equipment. One of the standout features of NiCd batteries is their resilience to extreme temperatures, functioning efficiently in both hot and cold environments.

Their robustness allows them to sustain a significant number of charge and discharge cycles—typically around 1,000 or more—before their capacity begins to diminish. This durability, paired with a relatively low cost, has cemented their position as a favorable choice for various industrial and consumer applications. However, it’s essential to consider the environmental impact associated with NiCd batteries. Cadmium is a toxic heavy metal, which poses disposal challenges and potential environmental hazards.

Manufacturers and users alike should be mindful of proper recycling protocols to mitigate any adverse effects on the environment. In terms of maintenance, NiCd batteries exhibit a phenomenon known as the “memory effect,” whereby they may lose capacity if not fully discharged before being recharged.

To maximize their lifespan and performance, it’s advised to occasionally allow the battery to complete a full discharge cycle. In summary, Nickel Cadmium batteries offer a blend of dependability, temperature tolerance, and rechargeability that makes them a vital player in the commercial battery landscape.

Understanding their unique characteristics enables users to leverage their advantages effectively while remaining cognizant of their environmental implications. For those exploring options in commercial batteries, the NiCd battery remains a critical component of the conversation.

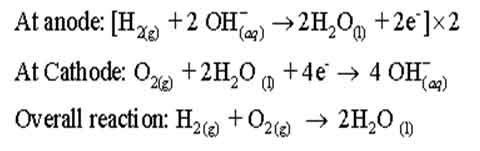

Fundamentals of commercial batteries Fuel cell

Electrical cells that are designated to convert the energy from the combustion of fuels such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, or methane directly into electrical energy are called fuel cells. One of the most successful fuel cells uses the reaction of hydrogen with oxygen to form water. It has been used for electric power in the Apollo space program. The water vapor produced was condensed and added to the drinking water supply for astronauts. Its efficiency is very high. In the cell, hydrogen and oxygen are bubbled through a porous carbon electrode into concentrated aqueous sodium hydroxide. Catalysts are incorporated into the electrode

Corrosion

The process of slowly eating away of the metal due to attack of the atmospheric gases on the surface of the metal resulting in the formation of compounds such as oxides, sulfides, carbonates, sulfates, etc. is called corrosion.

Factors that promote corrosion:

Reactivity of the metal more active metals is readily corroded.

The presence of impurities in metals enhances the chances of corrosion. Pure metals do not corrode e.g. pure iron does not rust.

The presence of air and moisture accelerate corrosion, the presence of gases like SO2 and CO2 in air catalyzes the process of corrosion. Iron when placed in a vacuum does not rust.

Corrosion (e.g. rusting of iron) takes place rapidly at bends, scratches, nicks, and cuts in the metal. Electrolytes also increase the rate of corrosion. For example, iron rusts faster in saline water than in pure water.

By applying a film of oil and grease on the surface of the iron tools and machine the rusting of iron can be prevented since it keeps the iron surface away from moisture, oxygen, and carbon dioxide

By electroplating the metal with other metals like Nickel, Chromium, etc.

Sacrificial Protection:

Sacrificial protection means covering the iron surface with a layer of metal that is more active (electropositive) than iron and thus prevents the iron from losing electrons. The more active metal loses electrons in preference to iron and converts itself into an ionic state. With the passage of time, the more active metal gets consumed but so long as it is present there, it will protect the iron from rusting and does not allow even the nearly exposed surface of iron to react.

The metal which is most often used for covering iron with more active metal is zinc and the process is called galvanization. The layer of zinc on the surface of iron, when comes in contact with moisture, oxygen, and carbon dioxide in the air, a protective invisible thin layer of basic zinc carbonate ( ZnCO3 . Zn(OH)2 ) is formed due to which the galvanized iron sheets lose their luster and also tends to protect it from further corrosion.

Electrical protection (Cathodic protection).:

The iron object to be protected from corrosion is connected to a more active metal either directly or through a wire. The iron object acts as the cathode and the the-protecting metal acts as an anode. The anode is gradually used up due to the oxidation of the metal to its ions due to the loss of electrons. Hydrogen ions collect at the iron cathode and prevent rust formation. The iron object gets protection from rusting as long as some of the active metal is present. Metals widely used for protecting iron objects from rusting are magnesium, zinc, and aluminum which are called sacrificial anodes.