Curriculum

- 12 Sections

- 69 Lessons

- 100 Hours

- Chapter 1 (Solid State)4

- Chapter 2 (Solutions)10

- 2.0Types of solutions20 Minutes

- 2.1Ways of expressing concentrations 120 Minutes

- 2.2Ways of expressing concentrations 220 Minutes

- 2.3Henry’s Law and applications 120 Minutes

- 2.4Raoult’s Law and applications 220 Minutes

- 2.5Colligative property 110 Minutes

- 2.6Colligative property 215 Minutes

- 2.7Colligative property 315 Minutes

- 2.8Colligative property 415 Minutes

- 2.9Abnormal Molecular Mass15 Minutes

- Chapter 3 (Electro Chemistry)8

- 3.1Electrolytic conductivity 120 Minutes

- 3.2Debye Huckel limiting law15 Minutes

- 3.3Electrochemical Cell20 Minutes

- 3.4Cell potential in electrochemistry20 Minutes

- 3.5How to use Nernst equation20 Minutes

- 3.6Gibbs free energy in electrochemistry20 Minutes

- 3.7Understand Faradays Laws of Electrolysis20 Minutes

- 3.8Fundamentals of commercial batteries20 Minutes

- Chapter 4 (Chemical Kinetics)6

- 4.1How to calculate rate of reaction20 Minutes

- 4.2How to calculate reaction law and orders20 Minutes

- 4.3Initial rate method know it all faster15 Minutes

- 4.4How to use integral method in kinetics 120 Minutes

- 4.5How to use integral method in kinetics 215 Minutes

- 4.6How Collision Theory Explains Chemical Reactions20 Minutes

- Chapter 8 (d-block Elements)7

- 5.1d block electron configuration charts10 Minutes

- 5.2Trend across d block 1 atomic radii10 Minutes

- 5.3Trend across d block 2 melting point10 Minutes

- 5.4Trend across d block 3 Ionization energy10 Minutes

- 5.5Trend across d block 4 Oxidation state10 Minutes

- 5.6Trend in d block 5 Electrode Potential10 Minutes

- 5.7Trend in d block metal properties

- Chapter 9 (Co-ordinate Compounds)6

- Chapter 10 (Haloalkanes Haloarenes)7

- Chapter 11 (Alcohols, Phenols Ethers)7

- Chapter 12 (Aldehyde Ketones)4

- Chapter 12 (Carboxylic acid, Derivatives)3

- Chapter 13 (Amines)3

- Chapter 14 (Biomolecules)4

How Collision Theory Explains Chemical Reactions

How Collision Theory Explains Chemical Reactions

Table of Contents

Introduction

Understanding the intricacies of how Collision Theory Explains Chemical Reactions can often feel like unraveling a complex puzzle, but at the heart of it lies a fascinating concept known as Collision Theory.

This fundamental principle helps us decode how and why reactions occur by focusing on the interactions between molecules. Whether you’re a student eager to ace your chemistry exam or a curious mind wanting to delve deeper into the science of reactions, understanding Collision Theory is essential.

In this blog post how collision theory explains chemical reactions, we will explore how this theory provides insight into the conditions necessary for chemical reactions to take place, the role of energy and orientation in collisions, and how it can help us predict reaction rates.

Join us as we break down the mechanics of molecular interactions and uncover the secrets behind the transformative nature of chemistry!

Molecularity

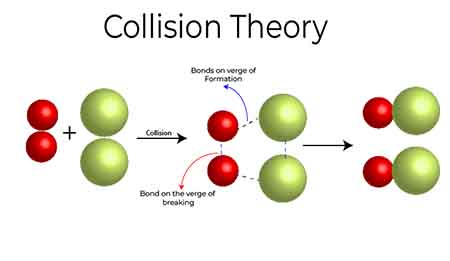

Molecularity is a fundamental concept in collision theory that helps us understand the intricacies of how Collision Theory Explains Chemical Reactions at the molecular level. It refers to the number of reactive species—atoms, ions, or molecules—that participate in a single collision event leading to a chemical reaction.

Essentially, in how collision theory explains chemical reactions, molecularity can be classified into three distinct types: unimolecular, bimolecular, and trimolecular reactions. In a unimolecular reaction, a single reactant molecule undergoes a transformation, such as decomposition or isomerization.

This type of reaction is crucial because it provides insight into how certain substances can spontaneously change under specific conditions. For instance, consider the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) into water and oxygen; this process is driven solely by the characteristics of the molecule itself.

Bimolecular reactions, on the other hand, involve the collision between two reactant species. This is perhaps the most common reaction type and showcases the importance of proper orientation and energy during a collision. In a simplistically illustrative example, when hydrogen gas (H₂) and iodine gas (I₂) collide, they can form hydrogen iodide (HI) through a bimolecular reaction catalyzed by light. The success of this reaction hinges on both molecules colliding with sufficient energy and the correct alignment.

Lastly, trimolecular reactions, while relatively rare, involve the simultaneous collision of three species. Such reactions often occur in gas-phase reactions where randomness and high concentrations of reactive particles create greater opportunities for simultaneous encounters. An example of this can be seen in the reactions involving ozone depletion in the atmosphere, where multiple gas molecules collide and react concurrently.

Understanding molecularity helps to illuminate the complexity and dynamics of how collision theory explains chemical reactions. By recognizing the roles of individual molecules in collision events, we can better anticipate reaction mechanisms, rates, and outcomes.

Types of reactions

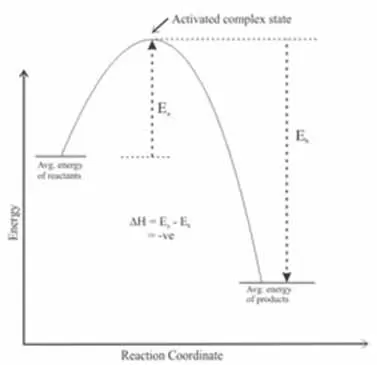

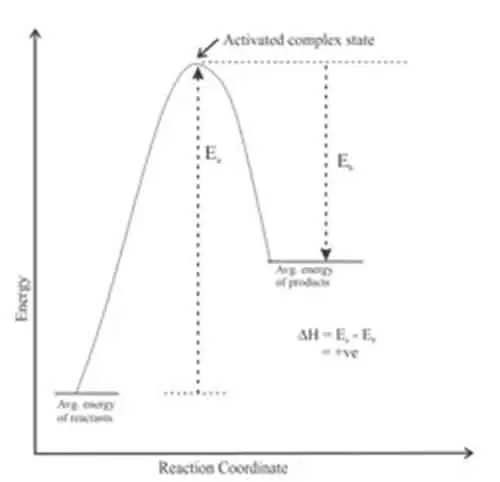

In the realm of chemical reactions, understanding how collision theory explains chemical reactions, the concepts of exothermic and endothermic reactions can significantly clarify how energy changes influence the rate and direction of a reaction.

According to how collision theory explains chemical reactions, for a reaction to occur, reactant molecules must collide with sufficient energy and an appropriate orientation. This energy is pivotal in determining whether a reaction is exothermic or endothermic.

Exothermic reactions are those that release energy into their surroundings, usually in the form of heat. When reactants collide and react, the energy absorbed during the bond-breaking phase is less than the energy released during bond formation.

Examples of exothermic reactions include combustion processes, such as burning wood or fossil fuels, where the energy released warms the environment. As the reactants convert to products, they release energy, leading to an increase in temperature that can be easily observed.

This release of heat can accelerate subsequent collisions, fostering an environment that enhances further reactions.

Endothermic reactions absorb energy from their surroundings, resulting in a decrease in temperature. In these cases, the energy required to break the bonds in the reactants is greater than the energy released when new bonds form in the products.

A classic example is the process of photosynthesis, where plants absorb sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen. In this reaction, the absorbed energy provides the necessary drive for the transformation to occur, emphasizing the significance of energy input in overcoming the activation barrier for the reaction.

Both exothermic and endothermic reactions elucidate vital aspects of collision theory.

Energy Barrier

The concept of the energy barrier is fundamental to understanding how collisions between molecules lead to how collision theory explains chemical reactions. According to collision theory, for a reaction to occur, reactant molecules must collide with sufficient energy and proper orientation. The energy barrier, often referred to as the activation energy, represents the minimum energy that reactant particles must possess to overcome this obstacle and transform into products.

Imagine a steep hill that must be climbed before reaching a lush valley on the other side; the energy barrier serves as that hill. Even if reactant molecules collide, if they do not have enough energy to surpass this threshold, they will simply bounce off each other, unable to evoke any change.

This concept becomes particularly crucial when considering temperature and concentration: as temperature increases, particles move more vigorously, thus providing them with more kinetic energy, which increases the likelihood of overcoming the energy barrier.

Collision Frequency

At the heart of collision theory lies the concept of collision frequency, a crucial factor determining the rate of chemical reactions. Collision frequency refers to the number of times reactant particles collide with one another in a given timeframe.

This is significant because, according to collision theory, for a reaction to occur, reactant molecules must not only collide but must do so with sufficient energy and correct orientation. The frequency of these collisions is influenced by several factors, including the concentration of the reactants and their physical states.

In a concentrated solution, for instance, reactant particles are more numerous, increasing the likelihood of collisions occurring. Conversely, in a dilute solution, the collision frequency decreases, leading to a slower reaction rate.

Understanding this concept is particularly useful for students learning about chemical kinetics, as it helps them grasp why some reactions proceed quickly while others take considerably longer.

Temperature also plays a pivotal role in collision frequency. As temperature increases, the kinetic energy of the particles rises, resulting in more vigorous movement. This increased activity not only leads to a higher collision frequency but also raises the probability that some collisions will have the necessary energy to overcome the activation barrier, allowing reactions to occur more readily.

Activation Energy

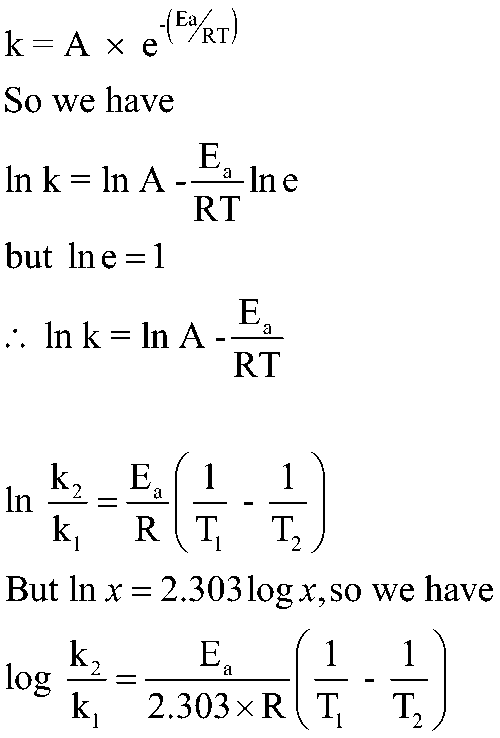

Simply put, activation energy is the minimum amount of energy required for reactants to collide in a way that will lead to a chemical reaction.

Think of it as the initial “hurdle” that must be overcome before the reaction can take place. In essence, for a reaction to proceed, the molecules involved need to collide with enough energy to break the existing bonds and allow new ones to form. The energy barrier presented by the activation energy can be viewed as a steep hill that reactants must climb before they can transform into products.

This threshold ensures that not every collision results in a reaction, explaining why certain reactions happen at particular rates under specific conditions. The amount of activation energy required for a reaction can be influenced by various factors, including temperature, concentration, and the presence of a catalyst.

Increasing the temperature, for instance, can supply more kinetic energy to the molecules, helping more of them reach or surpass the activation energy threshold.

Conversely, a catalyst lowers the amount of activation energy required, making it easier for reactions to occur and speeding up the process without being consumed.

Where:

K = Rate Constant

A= Arrhenius factor or collision frequency

Ea = Activation Energy

T1 < T2

At T1 → K1; At T2 → K2